“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so’ – Mark Twain

The movie Big Short opens with above quote, which sums up the danger of thinking you know something that isn’t actually true. There’s only one problem. There’s little evidence that Mark Twain actually said or wrote those words, which makes the irony all the more powerful.

The point is, many practices in financial services just aren’t supported by actual observed data on how investment markets work. (Which makes you wonder, where do they come from? But that’s a discussion for another day)

In a misguided attempt to manage sequence risk in retirement income portfolios, a great deal of effort is devoted to managing volatility. This has resulted in a vast number of ‘volatility managed’ funds and model portfolios peddled by asset managers to advisers and clients in retirement.

The trouble is, managing volatility in retirement portfolio is, for the most part, a red-herring. It’s a bit like bringing a knife to a gunfight.

In a retirement income portfolio, volatility isn’t your enemy per se. Sequence risk is. Sequence risk is often confused with volatility. I fell into the same error in my early days of researching retirement income strategies but looking the empirical data more closely I realise that, while the two are related, they’re very different.

- Volatility is the day-to-day gyration of a portfolio. It’s often measured using ‘standard deviation’ – the extent to which your portfolio’s returns deviate from the average over any given period of time.

- Sequence risk relates to the order in which portfolio returns occur. Specifically, the risk of having poor returns in early stage of retirement, even if good returns then show up in the later stage.

Volatility has very little impact on the order of returns. Two portfolios might have the same average return (mean) and volatility (standard deviation) over a given period of time, but if the order (sequence) of returns is different, then the sustainable income would be different.

Got it? OK.

[bctt tweet=”Managing volatility in a retirement portfolio is a bit like bringing a knife to a gunfight.” username=”AbrahamOnMoney”]

Want more in-depth research-based insight on retirement income? Join us at the Science of Retirement Conference on the 1st of March, 2017.

The Big Test

To measure the impact of volatility on sustainable income, I used the same dataset as my previous research; actual historical data over the last 115 years, between 1900 and 2015.

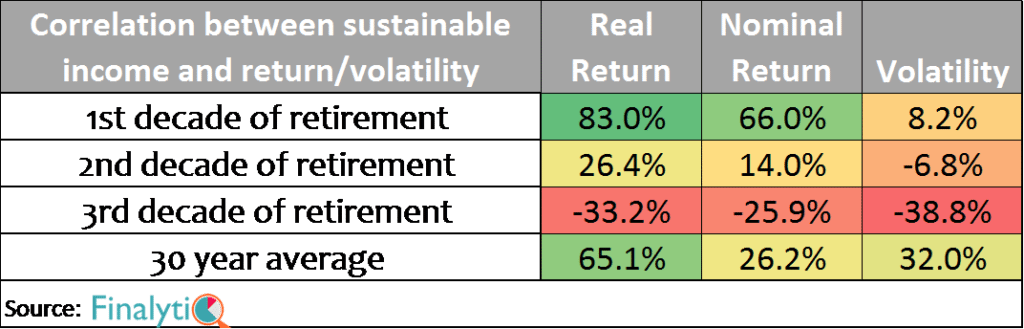

This time, I look at the relationship between historical sustainable withdrawal over any 30 year period and volatility obtained over each of the 3 decades of retirement within that 30 year period.

- For this, I looked at every 30 year period between 1900 and 2015 inclusive. So the first 30 year period runs between 1900-1929, then 1901-1930, 1902-1931… and final 30 year period runs between 1986-2015. This gives 87 scenarios.

- The portfolio is composed of 50% UK Equities and 50% UK Bonds, re-balanced annually.

- No fee has been applied but when I retested the result with fees applied, the findings hold regardless.

- I examined the correlation between average sustainable income and the volatility over 30 year retirement period.

The Result?

There is little correlation between volatility and sustainable income. Regardless of the period considered, income is as likely to be high and sustainable with a high volatility as it is with low volatility, provided the equity allocation in the portfolio remains constant.

While there’s a very strong correlation ( 83%) between returns in the first decade of retirement and the sustainable withdrawal over the entire 30-year retirement period, I find little correlation between volatility and sustainable income. There’s a less than 10% correlation between volatility in the first decade of retirement and the sustainable income over a 30-year period. Even when I examined the correlation between volatility over the entire 30-year period and sustainable income, I only found a 32% correlation! Sustainable withdrawal rate has little to do with volatility itself.

This is shocking! I know. It probably goes again everything you know about investing. I know. I know. I felt the same way.

Don’t just take my words for it. In an article published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Retirement in 2014, Kenigsberg et al carried out similar research using monthly historical data of US stocks and bonds. They noted….

To further test whether sequence of return (SOR) risk in the first decade overshadows volatility risk in determining the maximum Sustainable Withdrawal Rate (SWR), we ran a regression analysis on historical maximum SWR (as a dependent variable) first with the first decade’s real return and then with the first decade’s volatility as possible independent variables, using a 50/40/10 portfolio and the historical returns for the 702 complete 30-year periods between January 1926 and May 2014. We found that using the first decade’s real return as the independent variable produces an R2 value of 73%, whereas the regression using the first decade’s volatility yields an R2 of only 1%. Although the use of overlapping periods may complicate this statistical approach, we think the analysis at least suggests a greater influence from sequence than from volatility.

Investors may be tempted to use investment strategies designed to produce relatively low volatility (and accept the typically lower returns that come with them) during the early part of their retirements in order to minimize the probability of an adverse sequence of returns. But this is not necessarily effective. A strategy that produces low volatility may nonetheless deliver a highly disadvantageous sequence of returns because SOR risk and volatility, although not unrelated, are not the same thing. A poor SOR can just as easily be the product of persistence in returns (or autocorrelation) as of volatility.

A tale of two sisters

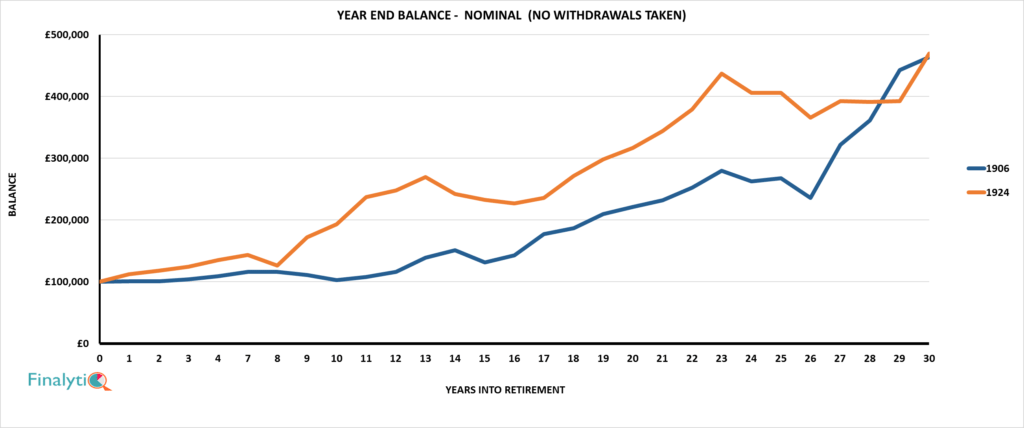

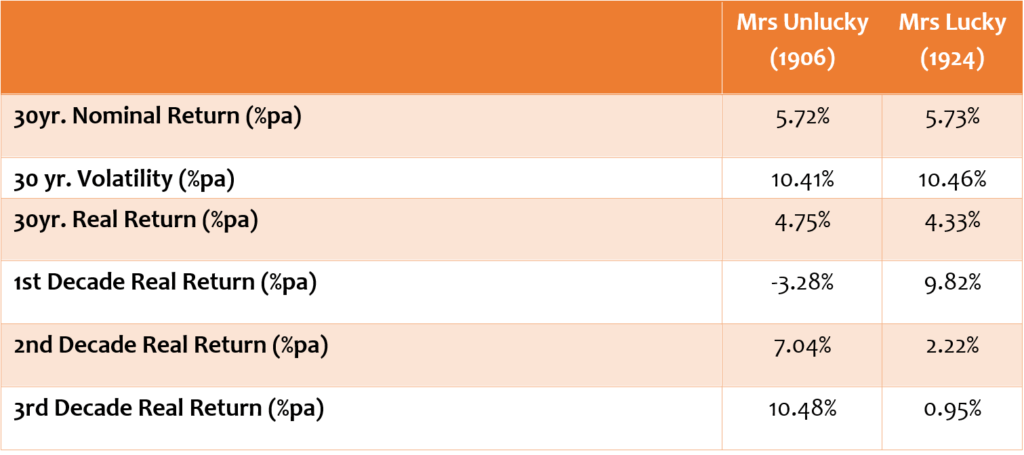

Take two hypothetical sister, Mrs Unlucky who started her retirement in 1906 and her much younger sister, Mrs Lucky who started her retirement in 1924. They both invested in a portfolio comprising 50% UK equities and 50% UK bonds.

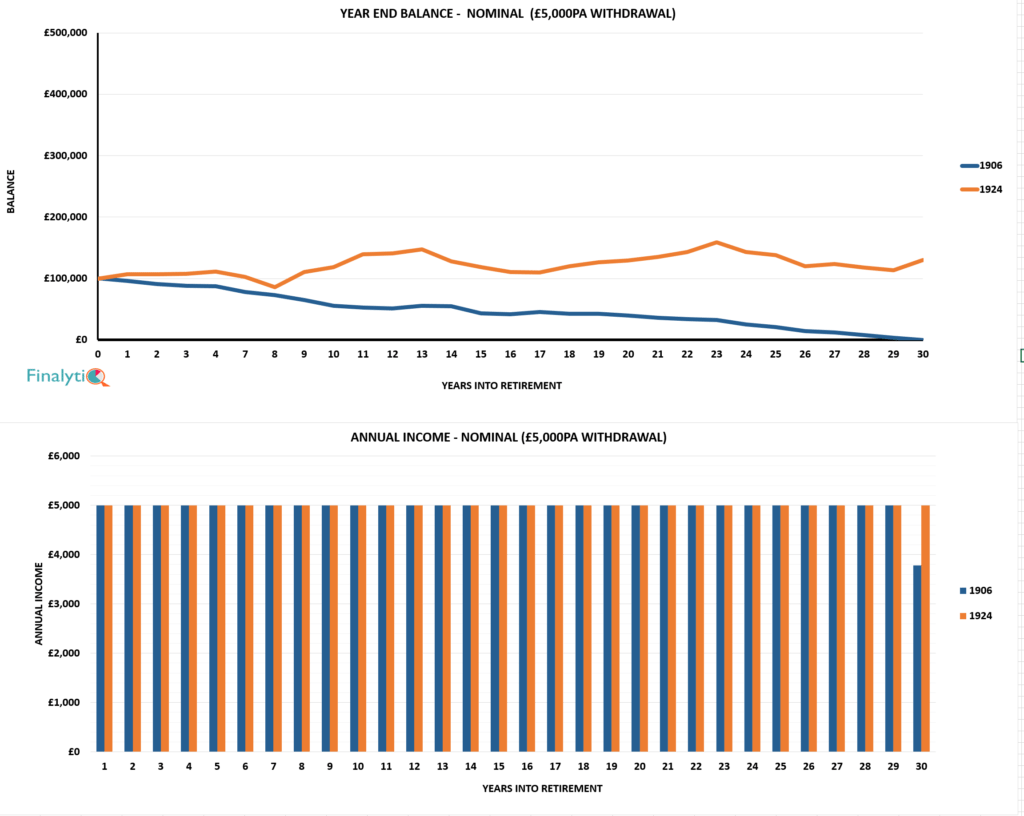

Over the subsequent 30-year period, they both enjoyed good average return of 5.7%p.a. (nominal) and very similar levels of volatility (about 10.4%) in their portfolio. Their real returns were also very similar, at over 4.3%pa. But in terms of actual sustainable income from their portfolios? It’s night and day! For some strange reason, Mrs Lucky’s portfolio would have supported an annual withdrawal of twice that of her sister over a period of 30 years.

The following chart shows what would have happened if both retirees took no income from their £100,000 portfolio over the subsequent 30-year period.

But suppose they both took an income of £5,000pa from their portfolios, without adjusting the withdrawal from inflation over a 30-year period? Mrs Unlucky (1906) ran out of money while Mrs Lucky (1926) ended up with more than her initial portfolio of £100,000!

How could that be? Same average returns. Same volatility. But very different experiences in terms of the income from their portfolios.

It’s very simple; Mrs Unlucky got stitched up by sequence risk. The order of return was unfavourable. The table below shows the summary of portfolio returns in both cases.

Look a bit more closely and you find that the returns in the first decade of their retirement were the key driver of the income over the entire 30-year period.

In the first decade, Mrs Unlucky got a return of -3.28%p.a. compared to Mrs Lucky’s 9.82%p.a. And it didn’t matter that Mrs Unlucky’s portfolio gave a decent return of 7.04%p.a. and 10.48%p.a. in the second and third decades of her retirement. The damage had already been done.

So, what?

Sequence risk is the primary investment risk in retirement. Not volatility. Controlling volatility doesn’t necessarily control sequence risk.

Many asset managers are barking up the wrong tree! The deluge of volatility-managed solutions designed for retirement income most likely won’t work. In fact, taking volatility off the table may end up being dangerous for retirees because it impairs return. Add to that the impact of high fees that these products typically charge, they may actually amplify the sequence risk rather than reduce it.

So next time a fund manager comes peddling a ‘volatility managed solution for retirement income‘, show them the door!

Nice challenge Abraham. Would you think that this may indicate a wave of compensation claims in about 10 years time?… as investors grill advisers about sustainable income levels retrospectively?

May I also ask if you are looking at calendar year-end data points? if so does the argument for sequencing not also apply to the start point in each of the 365 available days? if so are we not in danger of attempting to time the market by seeking the apparently more opportune moment to begin our first sequence?

I doubt very much investors understand the nitty-gritty of how volatility-managed funds, even retrospectively. But with a little help from professional ambulance chasers, anything is possible.

Yes, I did use annual data points and Kenigsberg et al used monthly data. Unless retiree is making withdrawal from their portfolio on a daily basis (no one does), I see no value in focusing on daily volatility or trying to time the market.

I guess the point is that you can’t control sequencing of returns. No amount of histoirlcal data analysis will tell you what is going to happen tomorrow. If you can control volatility though you can impact the magnitude of sequencing risk. If I build a portfolio that returns 5% with a volatility of 1% sequencing risk becomes pretty immaterial.

Both are important but it’s what you can do to manage them that is key

Hi Abraham, interesting article (and apologies in advance in case this is a daft question) but I wonder if you can clarify a point for me in relation to the first table looking at the correlation between sustainable income and returns/volatility. In each of the decades examined, and in the 30 years average, “real returns” are shown to be higher than “nominal returns”. Are the column headings just transposed or is there something else that I am misunderstanding?

Hi Al, the table is correct. Because withdrawals are adjusted for inflation, there’s stronger correlation between real return and withdrawal than between nominal return and withdrawal.

Abraham, in your view is it too simplistic to suggest that you just use Income units and take the yield that the underlying investments deliver, thereby avoiding excessive encashment of units in the early years????

Yield from income units is SO lumpy and unpredictable (not what many retirees want, preferring a steady, known “income”).

Secondly, total return is made up of capital appreciation and reinvested income. There is only ever one pie to slice, no matter how you slice it. Whichever way you take “income” out of a portfolio, it comes at the expense of something else.

Take two identical portfolios, based on one Equity Income fund yielding, say, 4%. One portfolio has acc units, the other inc. The acc portfolio withdraws 4% a year via unit-encashment; the other takes the floating yield of 4%. Come market crash or boom, the portfolios will be identical in value over time (assuming the withdrawals from the acc units are adjusted along the way to match the natural yield).

I tend to agree with Nick. I’m modelling the so called ‘natural yield’ portfolio and will post the result in coming weeks.

Hi Abraham. I love this article. Thank you for the insights. Looking forward to your results.

If one uses consumer focused dividend paying stocks the income yield is not lumpy and unpredictable. Same with listed property companies where the share price didn’t have a sharp run, pushing yield lower. Where the investor’s drawdown is matched to the natural/organic income yield of the portfolio, the client is living off income generated and not sacrificing units in the portfolio for income (or to manufacture annual income increases from capital). The result is that his unit balance stays in tact and therefore the investor gets the growth on those units. When units are sacrificed for income (especially early on) the portfolio’s ability to generate income is diminished over time, resulting in the whale graph. The client starts running out of money not because the funds s/he is invested in are performing poorly, it is because s/he is running out of units.

It really depends how wealthy were Mrs Lucky and Mrs Unlucky. Mrs Lucky could have been very unlucky if her husband died in the First World War. Worse even if her children died in the war, because they may have been her insurance policy!

I always take this type a research with a pinch of salt. Second thing after a quick read, I throw them in the bin. We are now in 2017, certainly not at the start of the First World War, may be at the start of a Trade War who God knows could start a real war.

The success and the failure of a retirement strategy is the result of the future economic activity. As long as Capitalism will still work, we may be OK. However with asset prices relatively high, people should behave cautious and this is the advice I dispense every day.

I always tell adviser to keep it simple and explain it in very simple words. Otherwise we end up telling clients all sort of jargon like sequence risk of returns, which we may believe we understand when in fact we understand little, because we deal with uncertainty.