Looks like The Great Guide to Risk-Rated Multi Asset Funds rattled the cage of asset managers, as intended. It’s fun to watch asset managers and their stooges fall over themselves to serve up their excuse why for they fail investors miserable.

They blame difficult market conditions. The Fed. Brexit. Bond Bubble. Does anyone ever wonder why when funds perform well, asset managers are quick to take credit but when they underperform, it’s the markets? I think it’s called self-attribution bias.

They blame me. For daring to do arithmetic. It’s the classic tactic to shut down someone if you don’t like what they are saying. You simply say that the person is wrong. You offer no alternative evidence or data or even cogent thought to prove an opposing point.

Then they blame the time periods. Apparently, it just so happened that none of the multi-asset fund ranges outperformed over any of the 1,3,5 and 10 year period we examined. Never mind that it’s a standard approach by investment researchers to look at multiple time periods in this way – S&P do this in their globally acclaimed SPIVA studies and Morningstar do the same in their Barometer studies.

Then they blame the data. One of them falsely claimed that the data is wrong because the couldn’t replicate it. As in, it’s factually incorrect. In actual fact, what he meant was he used a different index. I published my data and asked him to publish his. I’m still waiting.

Then they blame the benchmark. One thing that seems to drive them nuts is the idea of the Brainless Benchmark Portfolios which wiped the floor with multi-asset fund ranges, regardless of the time periods.

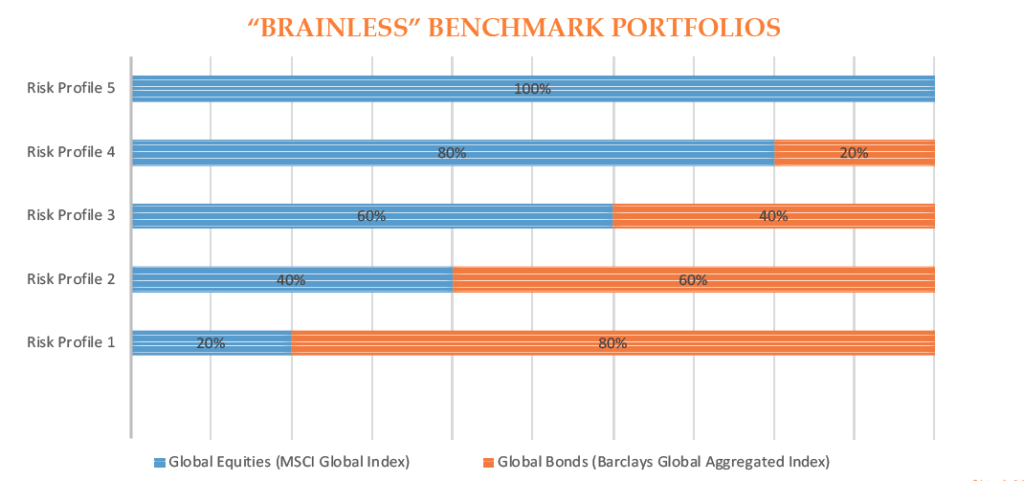

For our analysis, we created 5 ‘Brainless Benchmark Portfolios’ made up of percentage allocation to two asset classes – global equities and global bonds – as shown in the chart below;

The Brainless Portfolios have an annual fee of 0.50%pa and are rebalanced once a year on 1st January. The Brainless Portfolio is a passive portfolio in its purist form that allocates to market cap-weighted global equities and bonds, depending on the degree of risk an investor is prepared to stomach. In other words, they would take whatever return the market gives them rather than trying to make active predictions about which assets will perform better than others.

The ‘Brainless Portfolios’ depict the baseline return investors should expect for investing in a risk-based portfolio, because it doesn’t require any asset allocation or manager selection expertise. The only asset allocation decision our ‘Brainless Benchmark Portfolios’ require is what proportion of their portfolio should be invested in global equities and global bonds. They simply rebalance once a year on the 1st of January. And that’s it.

No tactical decisions. No allocation to property, commodities, alternatives or any other fancy stuff.

[bctt tweet=”The ‘Brainless Portfolios’ depict the baseline return investors should expect for investing in a risk-based portfolio.” username=”AbrahamOnMoney”]

The question we aimed to answer is, how do portfolios constructed by expert fund managers, asset allocators and Masters of the Universe compare with our brainless portfolios?

Well, here’s how…

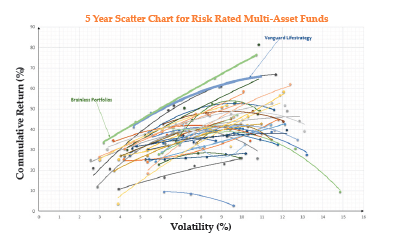

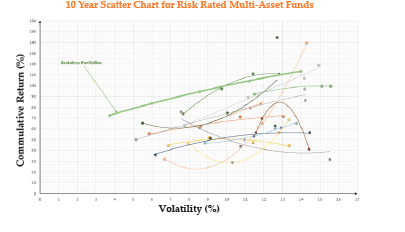

These scatter charts plot the cumulative return against the risk (volatility) of multi-asset funds. Each dot on the chart represents a fund. A polynomial trendline shows the risk-return relationship between all the funds in the same fund range. Each trendline on the graph represents an entire fund range, which consists of all the individual funds that make up the range. We refer to this trendline as the ‘Efficient Frontier’ for each fund range.

These scatter charts plot the cumulative return against the risk (volatility) of multi-asset funds. Each dot on the chart represents a fund. A polynomial trendline shows the risk-return relationship between all the funds in the same fund range. Each trendline on the graph represents an entire fund range, which consists of all the individual funds that make up the range. We refer to this trendline as the ‘Efficient Frontier’ for each fund range.

Fund ranges that lie below the ‘Brainless Benchmark Portfolio trendlines are sub-optimal because they do not adequately compensate clients for the level of risk associated with the fund. Portfolios that cluster to the right of the ‘Brainless Benchmark Portfolio’ trendline are also sub-optimal, because they take higher levels of risk for the level of return they deliver i.e. clients are taking more risks to get less return.

Did You Say Brainless?

The Brainless Portfolio is based on the concept of The Global Multi-Asset Portfolio (GMAP or Global Financial Asset Portfolio) which represents how the markets across the world allocate capital across publicly traded financial assets. The concept of GMAP been covered extensively in academic and practitioner research, notably by Ronald Doeswijk et al in their paper titled The Global Multi-Asset Market Portfolio, Meb Faber in his posts and book titled Global Asset Allocation, and this excellent post by Cullen Roche.

The global multi-asset market portfolio contains important information for strategic asset-allocation purposes. First, it shows the relative value of all asset classes according to the global financial investment community, which one could interpret as a natural benchmark for financial investors. Second, this portfolio may also serve as the starting point for investors who use a framework in the spirit of Black and Litterman (1992), or for investors who follow adaptive asset-allocation policies as advocated by Sharpe (2010). –

— Ronald Doeswijk et al, The Global Multi-Asset Market Portfolio

If there was such a thing as an indexing purist that person would simply buy all of the outstanding available financial assets in the world and call it quits. In other words, they would take what the market gives them rather than trying to make active predictions about which parts of the financial asset world will perform better than other parts.

— Cullen Roche, Is the Global Financial Asset Portfolio the Perfect Indexing Strategy?

The Brainless Portfolio is neutral. It’s how a novice investor should approach investing. Without any asset allocation expertise, a starting point should be to allocate their capital based on aggregate global market. And so it’s a perfect benchmark for multi-asset funds.

The Curse of Home Bias

This brings me to the next point. A few people criticise the Brainless Portfolio because ‘most multi-asset funds would have more allocation to UK equities.’

This misses the point. Deviating from the cap-weighted global equity allocation presumes that you know better than the aggregate of investors across the world. UK multi-asset fund managers exhibit home-bias by allocating more to UK equities, presumably because they have carried out thorough analysis about how best to allocate investors’ capital. And they know better than the markets.They can choose any asset class they want – commecial property, commodities, whatever. This is where their expertise lie. And since the proof of the pudding is in the eating, this should result in higher risk-adjusted returns. Except it doesn’t.

I don’t give a monkeys about why most multi-asset allocate more to UK equities or any other asset class. What I care about is whether they add value, over and above the Brainless Portfolios, through this asset allocation expertise.

To Hedge Or Not To Hedge A Global Portfolio

Another criticism of the Brainless Portfolio is that it hedges currency back to Sterling. The rationale is that, as a UK investor, you presumably earn and spend in Sterling. And so, while you are keen to benefit from the returns and opportunities offered by the aggregate publicly traded financial assets across the world, you are not prepared, as a novice investor to take currency risks.

So it makes perfect sense to me that a novice investor, using the Brainless Portfolio would take currency risk off the table by hedging back to their local currency. If not entirely, some of it. This is why many global bond funds offer a GBP hedge share class.

Someone on Twitter pointed out, without presenting any evidence, that most UK multi-asset managers don’t hedge currency risk in their portfolios.

Again, this is argument is pointless and doesn’t make the Brainless Portfolios wrong.

UK multi-asset managers are ‘experts’ and they make an informed decision to take currency risk. This adds another tool to their armoury. And since, the additional currency risk should be rewarded, this is yet another reason why multi-asset funds should outperform the Brainless Portfolios. Except that they don’t.

………..

One thing missing from fund managers and their stooges in this arguments is the data which shows that risk-rated multi-asset funds are indeed good value. They’ve presented none as yet. But I’ll be waiting. I’m here all day.

Asset managers don’t like being called to account. Most have a business model that profits from opacity and complexification. Which suggests to me that we’ll be in business for some time to come, because ours is a business model that profits from spreading the best disinfectant, sunlight, to the darkest corners of the investing world.

- To request a free excerpt of the report, just complete the form below and we’ll email you a copy

Powerful research! It was great to chat to you about this for our latest podcast episode, which went live this morning at https://www.icfp.co.uk/2016/09/informed-choice-radio-114-multi-asset-funds-vs-brainless-portfolios/

I’ll confess that I have not read the report and my comments are based purely on this blog and the various comments that I have read (here and elsewhere). There is a lot to commend in what Abraham has done and the ‘brainless’ benchmark approach has potential. However, I think that it is worth playing ‘Devil’s Advocate’ with one thought.

This is that all of the periods chosen end now. Therefore, all of the durations are mainly influenced by the current price – which right now is itself a reflection of multiple market highs in both equities and especially bonds (“the view always looks different from the top of the mountain”). In other words, they are all views from “top of the mountain”. To test varying market conditions it would be preferable to calculate moving 1 year, 3 year, 5 year and 10 year results over each of the last 20 years (I appreciate a lot more difficult). This is likely to reveal a more complicated story.

I am prompted to say this because of two experiences. Firstly, in the late 90’s, the reputation of ‘value’ managers took a beating because they were heavily under performing (over most durations) the UK market in particular. The story of Tony Dye at Phillips and Drew particularly comes to mind. By 2002 Phillips and Drew were among the best performing fund managers (over most durations) having been defensive throughout the post 2000 bear market but this was too late for Tony who was right (about 2 years early) but had already been fired.

The second is an even more dramatic example. In the late 80’s, global managers were also being beaten up for failing to beat the global index. At that time, the Nikkei was soaring to stratospheric levels (reaching nearly 40,000 in late 1989 and representing in excess of 50% of the global index) but for years, value managers in particular had urged caution and were ‘light’ on the Nikkei. Gartmore threw in the towel on their ‘value’ based strategy during 1989 and launched a passive global index fund, moving a lot of their discretionary client money into it (one of the biggest fund launches of that year). The Nikkei then plummeted nearly 60% to the 16,000 level by 1992 (which is roughly where it is today). Today the Nikkei is 8% of the global index. Global index investors over that period took a substantial ‘haircut’ whilst ‘value’ managers were finally vindicated.

Where are the market bubbles today? Some would say the USA (now 54% of the world index and propped up by truly massive Quantative Easing) but the really frightening ones are most of the world’s bond markets (now anything but safe).

I have no idea how many ‘multi asset’ managers follow a ‘value’ approach but if they are trying to provide some defence against these extreme market overvaluations, that may well be a price which clients are prepared to pay versus ‘defenceless’ benchmarks.