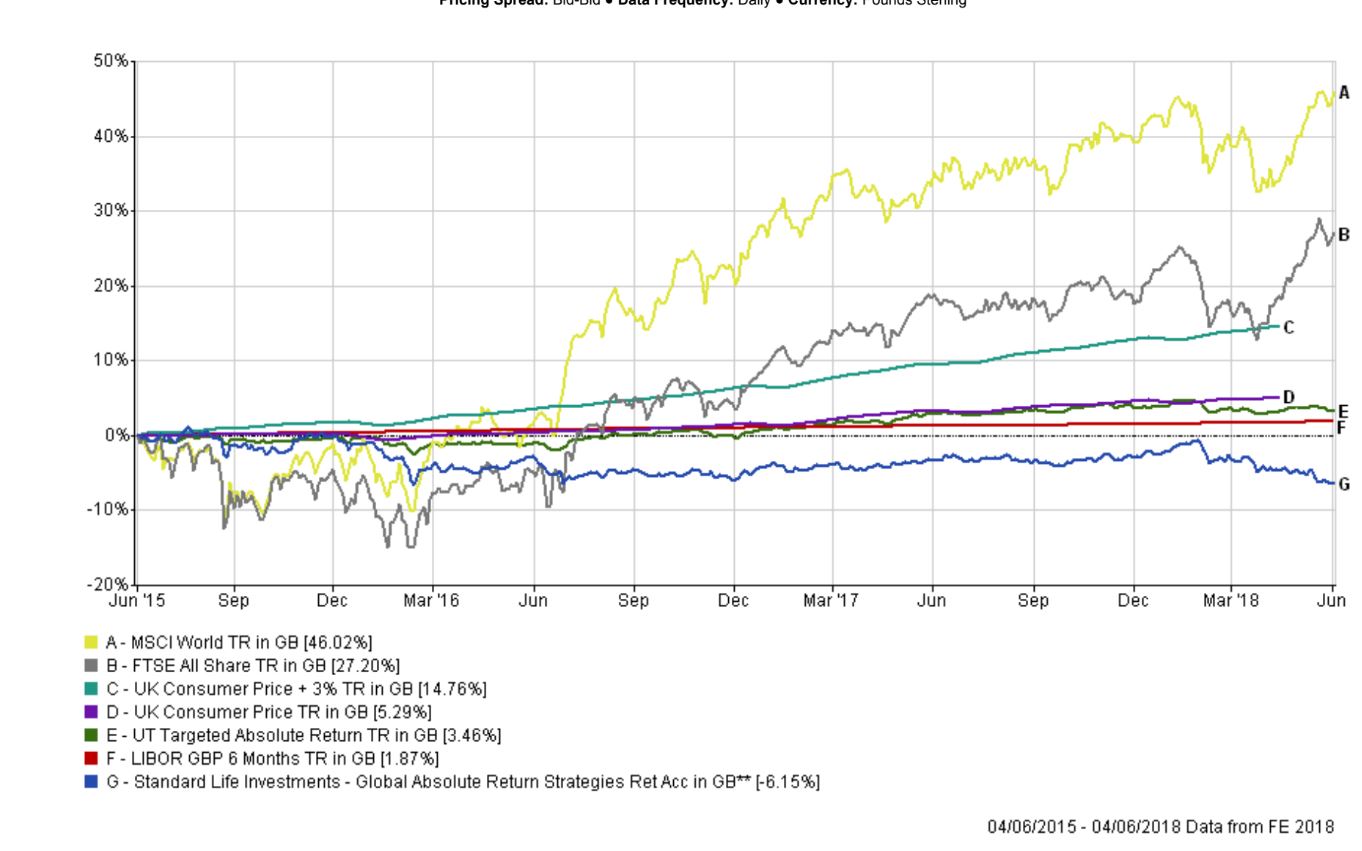

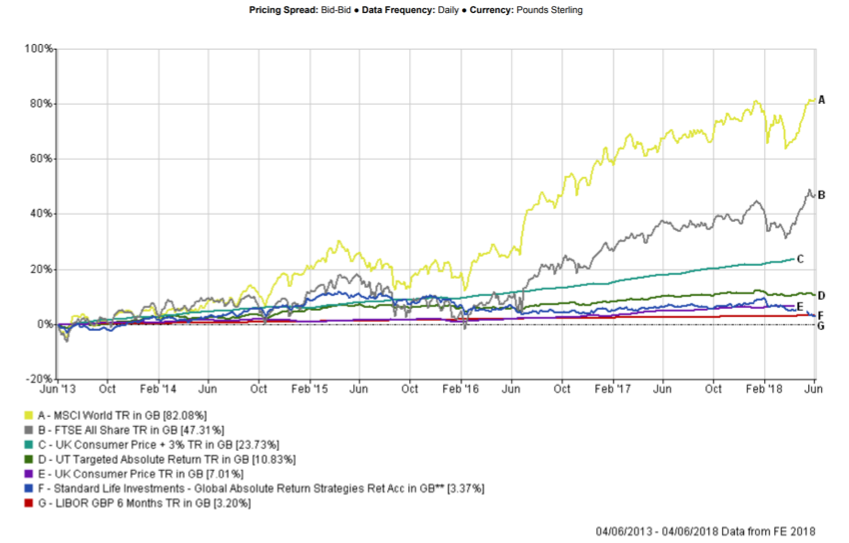

A recent article in the Guardian is the latest indictment of the Standard Life GARS fund. The fund has underperformed virtually all imaginable benchmarks over the last three and five years.

3-Year Cumulative Return

5-Year Cumulative Return

Is it just me or does anyone else remember a time that the fund was a top holding in many advisers and DFMs’ portfolios? If you weren’t holding GARS in your client’s portfolio, you weren’t cool. However, times have changed. It is far less popular these days. But with £20 billion in AUM, GARS remains a flagship fund for SLI/SLA (or is it ASI or CSI? We’re not really sure what to call them anymore). So let’s take a forensic look at some of the reasons people invested in the fund.

[bctt tweet=”Once upon a time, it was uncool NOT to hold GARS in your portfolio.” username=”AbrahamOnMoney”]

- Alternative to what?

When people say they are investing in ‘alternatives’, I get the feeling they have little clue what they’re talking about. By its very definition, investing in alternatives is often a bet against the equity markets. So, if you invest in alternatives, you should expect them to underperform during a raging bull market. And if you’re lucky, it’ll provide some downside protection in a bear market. Good luck with that. The problem with GARS (and those who invested in the fund) is that it promised equity-return for taking a cash-like risk – the fund aimed to generate positive (cash plus 5%) return in all market conditions! It has failed miserably. We all know you can’t have your cake and eat it and if it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

- Complexity breeds risk.

Hands up if you really understand how GARS works? Enough to explain it to a typical client? Veteran fund manager Alan Miller doesn’t. I certainly don’t. Many advisers and DFMs who invested in GARS didn’t. I’ll wager that many analysts/managers who work at the SL multi-asset teams and indeed the most senior people at SL don’t either. This explains why it became harder and harder for them to turn the fund around once it started going south after the original team left.

Now, if all these professionals don’t seem to understand the fund, what hope has the poor, old Mrs Miggins got? Legendary investor Warren Buffet once admonished us to “never invest in a business you cannot understand.”

The investment industry loves complexity, driven by the twisted belief that complexity should earn a higher fee! But complexity breeds risk. Complexity makes it harder for investment teams to explain their own strategy. It makes it harder for advisers to conduct adequate due-diligence on a product. And the investor is worse for it. It’s the classic lose-lose-lose.

[bctt tweet=”The investment industry loves complexity, driven by the twisted belief that complexity should earn a higher fee! .” username=”AbrahamOnMoney”]

- Manager risk.

Things really began to go south for GARS when its architect Euan Munro left SLI to run Aviva Investors, taking some of his team with him. One of Munro’s first acts at Aviva was to… you guessed it… launch new funds to rival GARS. He was swiftly followed by managers Richard Batty and Dave Jubb who were poached by Invesco to set up a rival fund. They have since attracted a whopping £10billion into their new funds, much of which came from GARS!

The lesson here is, investors who place their faith in active managers also bear the risk of any movements these managers may make during their careers. And unfortunately, the more complex the strategy, the harder it becomes to maintain consistent outcomes when the manager leaves. Anchoring your financial future on the career decisions of a manager seems like a bad strategy if you ask me.

- Success breeds failure.

One fundamental problem with asset management is diseconomy of scale; size tends to eventually hurt performance. This is particularly true for funds with complex strategies. In its glory days, GARS topped £26billion in size. This creates a problem of too much money chasing too few ideas. But it’s also against the interest of the fund houses to stop accepting money into a growing fund. This creates a conflict of interest between the fund and the investors.

- Vertically-conflicted

While the fund continues to haemorrhage money, it’s fascinating that SL continues to feed this beast of a fund. GARS continues to be a top-three holding in SL’s MyFolio, MPS and 1825’s models! Some MyFolio funds allocate as much as 20% of the total holding to GARS alone!

This highlights inherent conflicts of interest in vertically-integrated models. If SL drops the funds from its portfolios, that could be seen by other investors as an admission of defeat by SL. So they keep pilling investors’ money in. Only time will tell, but I’m pretty sure there’s a special place in hell for those who put corporate interest above that of the client’s!

Those advisers that strayed from GARS are feeling vindicated, as they should. But sadly, clients rarely thank their advisers for avoiding the flavour of the month. They may ask why a particular fund that has performed rather well lately isn’t in their portfolio. But they don’t send you a ‘thank you’ note for avoiding the current investment fad when everyone’s pilling in. They bloody well should.

[bctt tweet=”Clients rarely thank their advisers for avoiding the flavour of the month. They bloody well should..” username=”AbrahamOnMoney”]