“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future!” Niels Bohr

Human beings love to make predictions. Just look at the extraordinary growth of the gambling industry. Twenty-four hours a day, you can place a bet on anything from the number of throw-ins in a football match to the colour of the Queen’s hat at Ascot.

But there’s a problem – and a reason why online betting is one of the most profitable sectors in the economy. It’s that most of us aren’t very good at it.

Ask Professor Philip Tetlock at the University of Pennsylvania. In the mid-1980s, he began one of the longest and most detailed studies ever carried out into the accuracy of predictions made by experts across a number of fields, including politics, the economy and finance.

Fooled by Randomness

In 2005, he concluded that the forecasts he analysed were statistically indistinguishable from random guesses. “It is impossible,” he wrote, “to find any domain in which humans clearly outperformed crude extrapolation algorithms, less still sophisticated statistical ones.”

Of course, the fact that we can’t predict the future doesn’t stop us believing that we can. This tendency was observed by psychologist Ellen Langer in a series of experiments during the 1970s. In one, she asked a group of students at Yale to watch someone toss a coin 30 times and call the toss as either heads or tails.

Langer then asked the students how well they thought they might do if the exercise were repeated. Students who had experienced a pattern of success had a higher opinion of their coin-toss forecasting skill and felt that they would shine again.

That’s right: they were fooled into believing that they had the power to predict entirely random outcomes based solely on their past immediate success.

Langer dubbed this tendency “the illusion of control”; and you only need to browse through the financial pages of national newspapers at this time of year to see that the phenomenon is alive and well in the world of investing.

Lessons of 2020

You might have thought that last year, of all years, would have taught us to be wary of making financial forecasts. Twelve months ago, few financial forecasters were predicting that a then obscure virus in a remote corner of China would morph into a pandemic that would ravage the global economy.

Neither did forecasters expect that Brent crude prices would plunge to their lowest levels in more than 20 years at one point below $US16 a barrel as governments put their economies in hibernation, sending oil demand into a deep freeze.

Source: US Energy Information Administration (2020)

But this is the problem with forecasting. You start with a set of macro-economic assumptions about economic growth, interest rates, currencies, commodity prices and household demand, then overlay a bunch of micro-economic assumptions about industry supply and competition. Finally, if you’re a stock picker, you analyse company fundamentals like cash flow and debt-equity ratios and market position.

None of this can ever take account of the possibility, however remote, of “black swan” events like wars or political crises, natural disasters or pandemics.

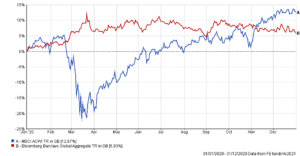

And even if these events were predictable, guessing what impact they might have on the markets is another huge challenge. Who would have thought, for instance, when global markets plummeted in March 2020, that most of them would recover and reach new heights as quickly as they did?

Source: FE Fundinfo (2020)

A Better Way To Invest

So, if the future is unknown, even by the best forecasters, and if even the most meticulous financial plan can be undone by bad luck, what can we do?

Well, it starts with acknowledging what we don’t know. There’s nothing wrong with having opinions. But realistically, do we have any unique insights that can genuinely give us an edge?

Do we know what the future has in store for the economy? Are we more informed than the world’s top virologists on how long it will take to bring the pandemic under control? Can we predict how the recently signed Brexit deal will impact the UK economy in the long term?

The team at FinalytiQ would love to have the power of clairvoyance, as well as other psychic powers, fortunately we are humble enough to accept that we cannot predict the future and thus must answer “no” to all the questions posed above. Hence, we don’t try to pick asset classes, sectors of funds that we “believe” will outperform their peers.

Instead we focus on things that we can control by using decades of research to build low cost, globally diversified, market weighted capitalised portfolios that have the best possible chance of delivering long run returns for investors.

References

Langer, E. J. (1975). The illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(2), 311-328.

Tetlock, P. E. (2005). Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? Princeton University Press.

What to expect from us 2021

Please take a look at our updated FinalytiQ Service Agreement.