There’s a misconception about evidence-based investing that I come across all time. People assume that choosing low-cost index funds means you believe that no one can beat the market. That’s simply not true. The difficulty is identifying managers who do before the event and having the discipline to stick with them long enough for that bet to pay off. Evidence-based investing simply realizes that the probability of overcoming these hurdles is simply too high for most mortals.

The passive vs active debate has raged since the first ever index fund was launched in the US in 1971. And it’s been centered on whether there are managers who have the skills to outperform the their benchmarks. However, latest research has shifted the debate to whether an investor or an adviser has the skills and more importantly the emotional fortitude to successfully identify these managers and stay the course. Evidence simply suggests that most people – advisers and investors – simply don’t.

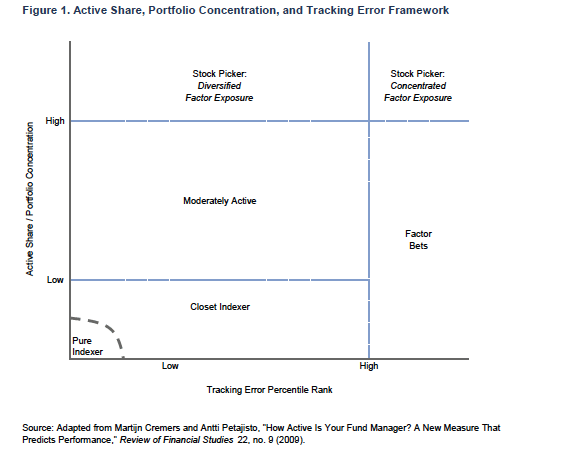

A new report by institutional investment consultants Cambridge Associates, titled Hallmarks of Successful Active Equity Managers attempts to provide a robust framework for selecting active equity managers. The framework is designed for institutional investors but applicable to retail investment advisers alike. It focuses three core metrics;

- High Active Share: Drawing on the work of Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto[1], the first step is identifying managers with high active share. The report suggests identifying managers with at least 80% active share for large cap funds and 95% or more active share for smaller companies funds. On average, a typical large cap fund meeting this criterion outperforms their benchmark by 0.29% pa, net of cost!

- Portfolio Concentration: Managers with highly concentrated portfolios have greater potential to outperformance [2]. For large cap funds, the author recommends portfolios with a maximum of 30 holdings and a limit of 40 holdings for small cap funds.

- Tracking Error: Avoid high active share funds with extreme tracking errors, as this can sometimes indicates the outperformance is highly dependent on a narrow industry or factor bets that may go in and out of fashion (as against desirable and established factors such as value, size and momentum, with well documented long-run performance benefits.)

Combining these key manager selection criteria, you end up with a framework that could be consider the ‘Holy Grail’ of active manager selection;

The real gem in the report however, is on the last few pages, where the author highlighted the constraints of implementing these strategies.

- Truly Skilly Active Managers Are Rare

The paper highlighted the fact that there is a very limited supply of managers who actually meet these criteria. Just 20% of the assets managed in US equity funds over the last decade were held in funds with more than 80% active share. And less than 10% of the active equity managers in the author’s own sample met the definition of concentrated portfolio used in the analysis.

So here the question, what proportion of equity managers in any particular sector will meet these criteria of high active share, high concentrated portfolio without extreme tracking error? The answer is very few and this somewhat confirms earlier studies that these managers are far and in-between.[3]

Fund management is all about scale. Funds that show exceptional outperformance tend to swell as investors flock in, making it even more difficult for the manager to maintain the outperformance. High active share funds, unfortunately do not lend themselves to scale. It’s easy for a £100m fund to be maintaining high active share and concentration; it’s a lot harder for a £1b fund to do.

‘Managers with differentiated portfolios face more significant career and business risk than benchmark-like managers.’

There is a reason why majority of funds are closet indexers. It may not be in the best interest of the investors but it’s a perfectly sensible business decision for the manager. The business risk that come with managers running high active share funds means that sooner rather than later, they are going to have to make the decision either to scale the fund (which often means becoming more of a closet indexer) or stick to their approach and possibly closing the fund to new inflows to stop it from becoming too big (which means the business is less stable and more susceptible to fund outflows when performance bleeps)

In effect this is asking the managers to choose between their own economic interest and their client’s best interest. What do you think they’ll do?

- Behavioual Errors Damage Returns

According to the author, high active share funds

‘create additional behavioral risk for the investors that hire them. Generally, relative performance and investor behavioral risk go hand in hand… Investors maximize their odds of success by remaining invested over a full market cycle, which is typically five to seven years. Rotating managers can leave an investor running in circles—and paying transition costs for the joy of doing it. The volatility of portfolios of high active share or concentrated managers can make investors more prone to exit at the wrong time, even if investors take our advice and exclude the ones with the most extreme tracking error.

In order words, the higher the outperformance of a fund, the more investors misbehave around the fund. The more a fund outperforms, the wider the gap between the return of that fund and the return of the investors/advisers choosing the fund. It is very difficult to design a process which aims to consistently pick winners and tolerate underperformance, albeit occasional, at the same time. How many advisers can tolerate underperformance for months, even years before they ditch a manager? Accordingly, even if you do succeed in picking these skillful managers, the net outperformance is likely to be destroyed by bad behavioral errors.

In summary, here’s my take;

- Are there managers with skill for outperformance? Yes, there are a few of them about!

- Can you locate these managers, before the event? Probably, but it’s a lot harder than most think. Past performance data won’t get you there.

- Do you have the discipline and fortitude, to implement a successfully framework without destroying the results with behavioral errors? Highly unlikely, most advisers and investors just don’t (and if you think you do, that makes it even more unlikely – it’s called illusory superiority)